LANDHOLDER RESOURCE GUIDE

Getting started with natural & assisted woodland regeneration

Rehabilitating any habitat from a modified or disturbed state requires strategic, well-timed intervention, observant monitoring, and a consistent methodical approach to obtain desired results. For the woodlands and forests on the New England Tablelands, historic and ongoing landscape modification has disrupted many of the natural processes that work to maintain functional woodland condition. As such, performing any woodland rehabilitation requires concerted efforts to qualify the current woodland condition, identify historic and ongoing disturbances that might limit natural processes, and intervene with appropriate land management practices to support natural or assisted woodland regeneration. While in theory this may seem relatively straight forward, the difficulty of making decisions to achieve desired results can be increasingly complex and challenging. Every landscape and landholder context is highly variable and requires individual consideration to better understand the need and type of rehabilitation works necessary. Working from principal understanding of processes that maintain woodland function allows for targeting of key areas that promote natural regeneration and the persistence of woodlands into the future (Goldney & Wakefield, 1997; Rawlings et al., 2010).

The woodlands and forests of the New England Tablelands face a variety of threats that have dramatically reduced their health and extent over the past 150 years of agricultural use. Some of these threats include tree dieback, fragmentation, exotic weeds, and overgrazing. These threats are well known scientifically, but also within the farming community, as the subsequent removal of trees from the landscape has been shown to negatively affect the overall ecosystem health and the ecosystem services provided by functional woodlands and native biodiversity. Revegetation and woodland-friendly farming practices that support natural regeneration are the main tools to stabilise and restore these threatened ecological communities (TECs). The good news is, we know how to do this, using techniques that promote natural and assisted regeneration that bolster, expand, and connect woodland areas. By re-introducing trees into the landscape we receive both short and long-term benefits that include erosion control, better infiltration of groundwater, habitat for beneficial local fauna, and nutrient retention within the soil. Furthermore, as our woodlands mature, the positive services they provide gradually increase, this, in turn, feeds back onto the farm directly affecting our capacity to produce high-quality products. By bringing trees back into our landscape, we are working to increase the resilience of these ecosystems that will be increasingly threatened by a future of climatic extremes.

The following sections provide a practical guide for landholders working towards woodland rehabilitation and aims to outline some tools and techniques complementary to conserving, improving, and expanding woodland habitat on the New England Tablelands. Specifically, this is tailored to the conservation of the two threatened ecological communities we work with, the New England Peppermint grassy woodland and the Ribbon-gum – Mountain-gum – Snow-gum Grassy Forest/Woodland but may be applied to other woodland community types on the tablelands. While we have aimed to provide the most up-to-date information and research within the field of performing natural and assisted woodland regeneration, this area of research is being continually expanded. We have presented several techniques that offer ideas about how landholders might perform natural regeneration in cost-effective and complementary ways to their current land management practices. We feel strongly that many farmers and landholders can achieve effective tree regeneration without it being restrictively expensive, technically difficult or at the expense of maintaining productivity.

Principles of Woodland Rehabilitation using Natural Regeneration

Woodland regeneration works largely follow the core principles surrounding improving woodland condition and extent in a fragmented landscape (Rawlings et al., 2010; McIntyre et al., 2004) . Where existing trees are healthy these are to be used for natural regeneration when conditions become favourable surrounding seeding events. To improve the success of recruitment events, fencing networks are used to exclude grazing stock and fertiliser applications to improve the probability of germination and protect maturing seedlings. Priority is given to sites most suited for regeneration including those with healthy adult trees, and areas adjacent to drainage lines, waterways and riparian zones that are a high priority for maintaining vegetation cover so as to reduce the probability of erosion. In designating areas for natural or assisted regeneration, increasing connectivity of woodland patches across the landscape should be prioritised, so as to reduce the impacts of edge effects on existing woodlands, and increase woodland habitat for flora and fauna.

Where remnant woodland occurs, first aim to protect and improve its health and extent so as to mitigate any further loss of habitat. By improving the health of woodland we aim to;

Improve canopy condition so the woodland has a higher probability of producing viable seed when conditions become favourable

Improve soil surface and herbaceous layer conditions by limiting stock access to minimise compaction, balanced with minimising the extent and severity of weed pressures that could limit the germination of new seedlings

Improve age-class recruitment i.e.; have multiple seedlings germinating and growing at different ages (classes) within the woodland area to assure a percentage of trees are mature and coming into maturity.

Minimising edge effects by increasing the woodland area size (woodland framework) so to mitigate the impacts of severe climatic and local weather conditions (wind, drought) on the woodland as a whole

Improving the diversity of species through the use of in-fill plantings of mid-story and understory species

Where woodland is fragmented, aim to connect existing island patches of woodland to larger wooded areas, first using natural regeneration and secondly using assisted revegetation (planting). The use of existing fencing networks is prioritised to limit costs.

Where lone paddock trees occur that present a healthy canopy cover (limited dieback, healthy foliage, greater projected cover), increase natural regeneration by linking to other paddock trees through the use of temporary fencing to exclude stock access and promote recruitment of seedlings. The use of existing fencing networks is prioritised to limit costs.

Plan for transitioning regenerating woodland areas to new potential sites suitable for natural or assisted regeneration when the desired level of new seedling recruitment has been obtained and seedlings are established. The use of existing fencing networks is prioritised to limit costs.

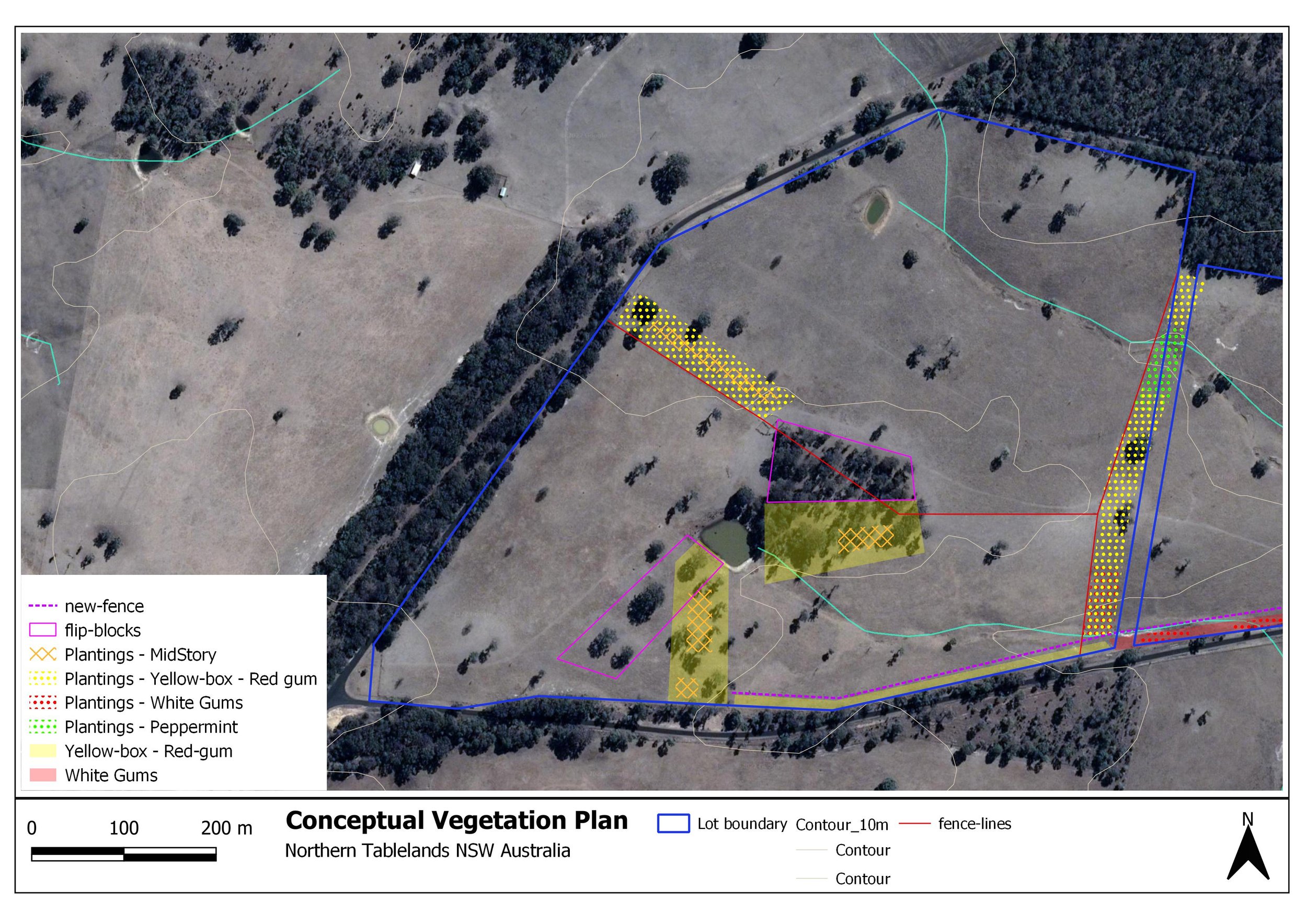

In order to put these principles into practice, the following sections step through a set of assessment and practical implementation tools that can be used to guide decision-making and on-ground works. Ultimately, a simple vegetation management plan will be developed that aims to identify woodland areas suitable for performing natural regeneration and outline a simple plan for connecting up habitat (Figure 1). These guides have been developed following tried and tested methodologies and aim to provide landholders with tools to perform natural and assisted woodland regeneration.

Figure 1: An example of a conceptual vegetation management plan that works to promote, expand, and connect woodland areas within a grazed and fragmented landscape. Note the use of temporary exclusion fencing to limit stock access to remnant woodland areas suitable for natural regeneration to occur. The use of plantings that include overstory and mid-story elements connect vegetation corridors together.

References

Goldney, D. C., & Wakefield, S. (1997). Save the bush toolkit. Environmental Studies Unit, Charles Sturt University.

Rawlings, K., Freudenberger, D., & Carr, D. (2010). A guide to managing box gum grassy woodlands. Commonwealth of Australia.

McIntyre, S., McIntyre, S., McIvor, J. G., & Heard, K. M. (Eds.). (2004). Managing & conserving grassy woodlands. CSIRO PUBLISHING.